Solidarity with the Sami People in Deatnu

We at CEMiPoS stand in solidarity with Ellos Deatnu, the Sami Parliaments of Finland and Norway, and the Sami Council fighting against the Norwegian and Finish authorities for their fishing rights in the Deatnu River.

The Deatnu River is a 250-kilometre-long subarctic river marking the border between Finland and Norway, accommodating approximately 30 genetically diverse wild salmon stocks. It is also the biggest and the most productive salmon river in Northern Europe.

In the seventeenth century, three siidas (local Sami communities that have existed from time immemorial) such as Ávjovárri, Deatnu and Ohcejohka governed the Deatnu River, banning non-siida members from fishing in the river. Since 1873, the Governments of Norway and Finland have replaced those siidas governing the river with various agreements. In 2017, a new agreement, which was passed despite opposition from the Sami, regulated the use of traditional Sami fishing techniques such as weir and net devices with a view to protecting/preserving salmon stocks.

In March 2017, shortly after the enforcement of the new agreement, Aslak Holmberg, a member of the Sami Parliament of Finland, sent a petition to the parliaments of Norway and Finland, arguing that the agreement was a clear violation of Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, and free, prior, and informed consent. The Sami Parliaments of Norway and Finland also protested, requesting support from international organisations and other Indigenous peoples. In July 2017, a new Sami activist group called Ellos Deatnu occupied an island in the Deatnu River, declared a moratorium on the fishing regulations, and organised a concert with celebrity artists in protest. Following their mobilisation, the Saami Council made its submission to the Human Rights Committee in March 2019.

Nonetheless, the governments of both Norway and Finland banned all fishing on the Deatnu River, its tributaries, estuaries and Finmark sea areas from May to December in 2021 due to the decline of salmon stocks in recent years. Holmberg protests the ban, insisting that: “Spawning has not fallen at the same rate as the numbers of returning salmon. The reasons for the decline must relate to their ocean migration. The salmon’s habitat in the Barents Sea has seen remarkable changes related to climate change in addition to overfishing” (Aslak Holmberg, Conserving Sámiland).

Faced with the contemporary climate crisis, the Sea of Okhotsk wedged between Siberia and Japan has warmed in some places by as much as 3 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, leading to the 70% plummet of the salmon catch in the past 15 years. Given that the Barents Sea has warmed at the same level, Holmsberg’s words should be taken into consideration. It is time for authorities in Norway and Finland to seriously heed his warning that if conservation efforts fail to acknowledge the historical, cultural, and ecological relationship between the Sami people in Deatnu and salmon, they will remain an extension of colonial action.

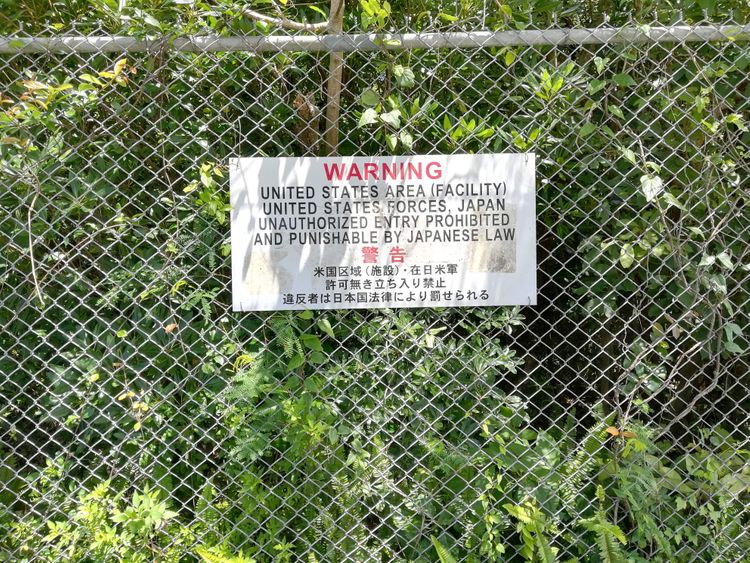

Header image courtesy of Ellos Deatnu -joavku